Available with Standard or Advanced license.

A relationship class contains several properties that define how objects in the origin relate to objects in the destination. You specify these properties when you create the relationship class.

- Type: Simple or composite

- Origin and destination classes

- Primary and foreign keys

- Cardinality: Is the relationship one-to-one, one-to-many, or many-to-many?

- Message notification direction, applicable if you want to implement custom cascade update or delete behavior

- Whether you want to store attributes for each relation

- Name

- Forward and backward labels that display when you navigate related records in ArcMap

Once you've created the relationship, you can specify rules to refine the cardinality.

Simple vs. composite

When you create a relationship class, you specify whether it is simple or composite.

In a simple relationship, related objects can exist independently of each other. For example, in a railroad network, you may have railroad crossings that have one or more related signal lamps. However, a railroad crossing can exist without a signal lamp, and signal lamps exist on the railroad network where there are no railroad crossings.

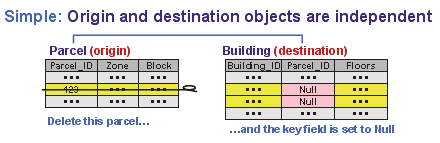

When you delete an origin object in a simple relationship, the foreign key field value for the matching destination object is set to Null. This foreign key behavior was designed to maintain referential integrity between features. If the origin feature is deleted, then the value in the foreign key is no longer relating that row to a feature in the origin and, as a result, the foreign key value is no longer required and is set to Null. The sole purpose of the foreign key is to maintain a relationship between the destination object and the related origin object. If there is no origin feature with the matching primary key value, then there is no reason to maintain the foreign key value. If you want to relate the same destination feature to a new or different origin feature in the future, the FK field can be updated from Null to the new FK value.

Deleting a destination object has no effect on the primary key value in the related origin object.

Simple relationships can have one-to-one, one-to-many, or many-to-many cardinality.

Like simple relationships, composite relationships also maintain referential integrity when objects are deleted, but they do so in a different way. In a composite relationship, destination objects can't exist independently of origin objects, so when the origin is deleted, the related destination objects are also deleted in a process called a cascade delete.

A composite relationship can also help you maintain features spatially; moving or rotating an origin feature causes the related destination features to move or rotate with it when messaging is set to Forward.

Composite relationships are always one-to-many when you create them but can be constrained to be one-to-one with relationship rules.

Origin and destination classes

When you create a relationship class, you choose one class to be the origin and another to be the destination. It is important not to confuse the two. With the behavior of cascade deletes in composite relationships, the importance of this may seem obvious.

In simple relationships, getting this correct is critical. This is because when you delete a record in the origin class, the simple relationship class finds the matching records in the destination class and sets the value of their key fields to Null. If you choose the wrong class as the origin and delete objects in the origin, you will introduce errors into the foreign key field. The following example illustrates how this can occur:

Case 1: Parcel to Zone (wrong)

This is a common scenario for error. The Zone table contains the descriptions for the various zoning codes and is conceptually similar to a lookup table. In this case, the Parcel class is the origin, and the Zone table is the destination. The problem is that when you delete a parcel, the value in the key field (Zone) is set to Null for the matching record in the Zone table, and none of the other parcels that have that zoning code have a match in the Zone table.

Case 2: Zone to Parcel (correct)

To correct the problem, set the Zone table as the origin. Deleting a parcel (a destination object) will have no effect on the Zone table, and deleting a Zone code (an origin object) will simply set the value of the Zone field in the matching parcel records to Null, which is as it should be, because they no longer have a matching Zone table record.

Primary and foreign keys

In a relationship class, objects in the origin match objects in the destination through the values in their key fields. In the following example, parcel 789 matches permits 2 and 3 because all those records have the same parcel ID.

The key field in the origin class of a relationship is called the primary key and is often abbreviated as PK. Unlike a true primary key, the values in the primary key field in a relationship are not required to be unique for every object.

The key field in the destination class is called the foreign key and is often abbreviated as FK. It contains values that match those of the primary key field in the origin class. Again, the key field values do not need to be unique for each row.

The key fields may have different names but must be of the same data type and contain the same kind of information, such as parcel IDs. Fields of all data types, except binary large object (BLOB), date, and raster, may be key fields. You specify the key fields when you create a relationship class.

When deciding on a primary key field, one option is to use the row ID field, commonly referred to as the ObjectID field. The ObjectID field is automatically added by ArcGIS when you create a feature class or table or register an enterprise geodatabase layer or table. This field guarantees a unique ID for each record. It is maintained by ArcGIS, and you can't modify it.

The ObjectID value of a given object never changes as long as it remains in its original class and, if the object is a feature, you do not split it. If you split a feature, it will maintain the original feature (but will update the geometry) and create a new feature, which will have a new ObjectID assigned to it. As a result, only the feature with the original ObjectID will maintain any relationships that are dependent on the ObjectID value.

Because of this, it may be better to create and use your own primary key field instead of relying on the ObjectID field. The following describes how your own primary key field can help maintain relationships when you perform each of these operations.

- When you import records to another feature class or table, new ObjectID values are assigned, losing any relationships based on the original ObjectID values. If, instead, you base the relationship on another primary key, the ID values in the primary key will not change when records import. This allows you to preserve relations when you import related sets of objects to new classes.

An exception is when you use the Copy/Paste function. Copy/Paste preserves ObjectID values, so if you plan to move objects with this method only, you can use the ObjectID field as the primary key.

- When you split a feature, the original feature is maintained (with updated geometry), and a new feature is created. If you have a relationship based on the original ObjectID, only one of the two features created in the split will maintain the relationship. However, if you used another field as the key, when you split the feature, the ID value of the original feature would be copied to the two new features. As a result, the records in the related table would now be related to both new features—ideal if the relationship class is set up as many-to-many.

If you won't be splitting features and are sure that all objects will remain in their original class, you can use the ObjectID as their IDs. If you can't guarantee this, it's best to set up and use your own ID field instead of relying on the ObjectID field.

- When you merge two features, the new feature retains the ObjectID of one of the original features. If you plan on merging features but not moving features out of their class or splitting them, you can use the ObjectID field as the primary key.

Cardinality

A relationship's cardinality specifies the number of objects in the origin class that can relate to a number of objects in the destination class. A relationship can have one of three cardinalities:

One-to-one—One origin object can relate to only one destination object. For example, a parcel can have only one legal description. In ArcGIS, this cardinality also covers many-to-one. An example of a many-to-one relationship is many parcels relating to the same legal description.

One-to-many—One origin object can relate to multiple destination objects. For example, a parcel may have many buildings. In a one-to-many relationship, the one side must be the origin class and the many side must be the destination class.

Many-to-many—One origin object can relate to multiple destination objects and, conversely, one destination object can relate to multiple origin objects. For example, a given property may have many owners, and a given owner may own many properties.

The terms one and many can be misleading. One is really zero-to-one, and many is really zero-to-many. So when you create a one-to-many relationship between parcels and buildings, for example, the relationship permits all of the following:

- A parcel with no buildings

- A building with no parcel

- A parcel with any number of buildings

Relationship rules

When you create a relationship class, you create it with the cardinalities one-to-one, one-to-many, or many-to-many.

A relationship often needs to be defined in more restrictive terms. In a relationship of parcels and buildings, for example, you might need to require that each building be associated with a parcel or that a parcel can contain a maximum number of buildings. You want to prevent a user from forgetting to associate a building to a parcel or from associating too many buildings to a parcel.

If you have subtypes, you can constrain the number and type of objects in the origin that can relate to a certain type of object in the destination. For example, steel poles support class A transformers, while wooden poles support class B transformers. Furthermore, you may also need to specify the permissible cardinality range for each valid subtype pair. For example, a steel pole can support 0–3 class A transformers, while a wooden pole can support 0–2 class B transformers.

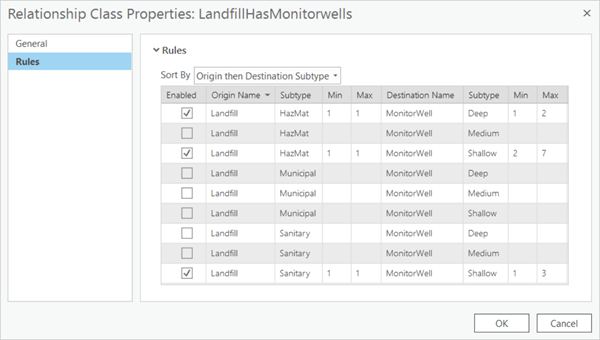

To view the relationship rules for your relationship class, right-click the relationship class in the Catalog pane to open the Relationship Class Properties dialog box and click the Rules tab.

This will show you a list of all of the possible rules that can exist for your relationship class. The Enabled column indicates which of the rules are currently active.

You can sort the relationship class rules in the display by selecting Origin then Destination Subtype or Destination then Origin Subtype in the Sort By drop-down menu.

To remove a rule from the relationship class, uncheck the Enabled check box for the row representing the rule you want to remove and click OK.

To create a rule on the relationship class, complete the following steps:

- Check the Enabled check box for the row that represents the rule you want to add to the relationship class.

- Set the appropriate Min and Max cardinalities on the rule for the origin and destination by entering integers in their corresponding cells.

- Repeat steps 1 and 2 for each rule that you want to add.

- Click OK.

Once a relationship rule is added to a relationship class, that rule becomes the only valid relationship that can exist. To make other relationship combinations and cardinalities valid, you must add more relationship rules.

In the example below, a HazMat landfill can be related to one or two deep wells or between two and seven shallow wells. However, if a sanitary landfill is related to a deep well, but no rule has been created between these two subtypes, the Validate Features command will consider the relationship to be invalid.

Message notification direction

As previously discussed, when you delete an origin object in a composite relationship, related destination objects are automatically deleted.

Whether you're working with simple or composite relationships, there may be other actions that require an update of one feature to trigger an update in its related features. Furthermore, updates can be required in one direction or another, or both.

- When you move or rotate a feature, you want related features to move or rotate along with it.

- When you update a feature, you want an attribute in a related feature to update automatically.

- Updating an origin can require related destination objects to update.

- Updating destination objects can require related origin objects to update.

If your relationship requires this behavior, you can have origin and destination objects send messages to notify one another when they are changed, allowing related objects to update appropriately.

To accomplish this, set the message notification direction when you create the relationship. If updating an origin requires related destination objects to update, set the message notification direction to Forward. If updating the destination requires related origin objects to update, set the message notification to Backward. If you require both of these, set the message notification direction to Both. Once you've created the relationship, you must program behavior into the objects that receive the messages so they can respond.

The only exception is composite relationships when messaging is set to Forward. When you create a composite relationship with forward messaging, moving or rotating an origin object causes related destination features to automatically move or rotate along with it. Provided you set up your relationship correctly, this functionality works as soon as you've created the relationship—no custom programming is required.

For other message notification directions, custom programming is required. Unless you're creating a composite relationship with forward messaging or are intending to program custom behavior, set the message notification to None. Otherwise, messages will needlessly generate each time you perform an edit operation, slowing performance.

When setting the direction for composite relationships, keep in mind that when the origin object in a composite relationship is deleted, all related objects in the destination are automatically deleted. This happens regardless of whether messaging is set to Forward, Backward, Both, or None.

| Direction | Effect on simple relationships | Effect on composite relationships |

|---|---|---|

Forward | No effect unless customized with programming |

|

Backward | No effect unless customized with programming |

|

Both | No effect unless customized with programming |

|

None | Prevents messages from being sent, slightly improving performance |

|

Many-to-many relationships

In one-to-one and one-to-many relationships, values in the primary key of the origin class directly relate to values in the foreign key of the destination class.

Many-to-many relationships, on the other hand, require the use of an intermediate table to map the associations. As a result, when you create a many-to-many relationship, an intermediate table is automatically created. The intermediate table maps primary key values from the origin to foreign key values from the destination. Each row associates one origin object with one destination object.

When the intermediate table is created, only the fields are generated for you. ArcGIS does not know which origin objects are associated with which destination objects, so you must manually create the rows in the table. Populating this table is the most time-consuming part of setting up the relationship.

Relationship attributes

The intermediate table of a many-to-many relationship can optionally serve a second purpose—storing attributes of the relationship itself. For example, in a parcel database, you may have a relationship class between parcels and owners, where owners own parcels and parcels are owned by owners. An attribute of each relationship could be the percentage of ownership. If you need to store such attributes, you can add them to the intermediate table when you create the relationship or anytime after.

Although not as useful, when you're setting up a one-to-one or one-to-many relationship, you may have the same need to store attributes of the relationship. If this is the case, you must specify this when you create the relationship so an intermediate table is created for you. As with many-to-many relationships, the intermediate table maps primary key values from the origin to foreign key values from the destination, allowing you to store any number of attributes for each relation.

If you add the relationship class to the Map, it will appear as a table that you can open and manipulate. ArcGIS does not expose the intermediate table for other operations. For example, you cannot display its properties in the Catalog pane, or add or delete fields in the Fields view, and it doesn't support the use of default values or domains.

Name

Each relationship class has a name that displays in the Catalog pane. To make the database structure easy to understand, name the relationship class so the name describes the relationship.

Start with the name of the origin feature class, follow with Has or Have, and end with the name of the destination feature class. For example, AddressHasZones or ParcelsHaveOwners. Pluralize the origin feature class name if it is a many-to-one or many-to-many cardinality, and pluralize the destination feature class name if it is a one-to-many or many-to-many cardinality.

Using this method, you can determine the cardinality of a relationship class from its name. For example, with both feature classes in the plural, ParcelsHaveOwners suggests a many-to-many relationship.

Forward and backward labels

Forward and backward labels display on the Attributes and Identify results dialog boxes in the Map pane and help you navigate between related objects.

A relationship class has two labels:

- A forward label that displays when you navigate from the origin to the destination. In the pole–transformer example, this label could read "supports", meaning this pole supports these transformers.

- A backward label that displays when you navigate from the destination to the origin. In the pole–transformer example, this label could read "is mounted on", meaning these transformers are mounted on this pole.